Rust in Anger

TL,DR: if you’d like to quickly call Rust code from Python, TypeScript or Node.js, fork this GitHub project.

Introduction

We’ve been using Rust in anger for a couple of years now in some sophisticated SaaS products, such as IronCalc, our “spreadsheet as a service” platform for developers. It’s been great to leverage a fast, memory-safe, and versatile programming language like Rust in our Python, Rust and Node.js code-bases. Here we’ve collected our insights so that others can benefit from our experience.

Accompanying this post is a GitHub repository with all the relevant code. This serves two purposes: to help you understand what’s going on as you read the post, and to give you a quick start with your own project.

Move beyond isomorphic JavaScript (a term I don’t particularly like)! Write Rust code that is compiled to run on both on the server and client side without any significant overhead.

Common problems: sending and receiving values

Applications often require serialization and deserialization logic to pass data between different programming environments. For example, a JavaScript application in the browser serializing JSON data that is sent to the server, where it is deserialized and interpreted by some Python application logic.

In our case we want TypeScript to send an “input” object to Wasm, which Wasm will use to compute an “output” object that it returns to TypeScript. To make things a bit more concrete let’s say we are developing an application that deals with triangles. From the TypeScript perspective we will have definitions like:

type Point {

x: number;

y: number;

};

type Triangle {

tag: string;

p1: Point;

p2: Point;

p3: Point;

}

Consider this line of code:

const newTriangle = scaleTriangle(triangle, scaleFactor);

The function scaleTriangle has the signature (triangle: Triangle, scaleFactor: number): Triangle and transforms a Triangle so as to scale it in accordance with scaleFactor. To do this, Wasm code is called - however, Wasm does not work with rich types, only Numbers and vectors thereof. So, in order to call this from TypeScript, we must:

- Serialize inputs in TypeScript: Our TypeScript code must serialize the parameters into something the Wasm code can consume. Typically a vector or u8.

- Deserialize inputs in Wasm: The Wasm code deserializes the parameters

- Compute outputs in Wasm: The Wasm code executes, computing the outputs.

- Serialize outputs in Wasm: Once the Wasm code completes, it serializes its output in a format understood by TypeScript

- Deserialize outputs in TypeScript: TypeScript will then deserialize the output

There are several ways to implement 1-5, with the best strategy determined by considering the trade-offs. In our particular case, we are serializing/deserializing “small” amounts of data, and relatively infrequently, so we will use the method most convenient from the perspective of implementation.

The following bindings allow for the most efficient serialization / deserialization of data:

function scaleTriangle(t: Triangle, scaleFactor: number) : Triangle {

const [p1x, p1y, p2x, p2y, p3x, p3y] = wasm.scaleTriangle(t.p1.x, t.p1.y, t.p2.x, t.p2.y, t.p3.x, t.p3.y, scaleFactor);

return {

tag: t.tag,

p1: {x: p1.x, y.p1y},

p2: {x: p2.x, y.p2y},

p3: {x: p3.x, y.p3y},

}

}

This is a nice way to get started— but it could become difficult to maintain down the line. Let me be clear: this isn’t necessarily a bad strategy. For small to medium-sized projects, it might even be the best option, as it adds no dependencies and is easily understood. However, for code that is not performance sensitive, I’d recommend the “types” abstraction since it saves you from manually maintaining the bindings. This would mean the wrapper above wouldn’t be required, and you could directly call an auto-generated JavaScript wrapper:

const newTriangle = scaleTriangle(triangle, scaleFactor);

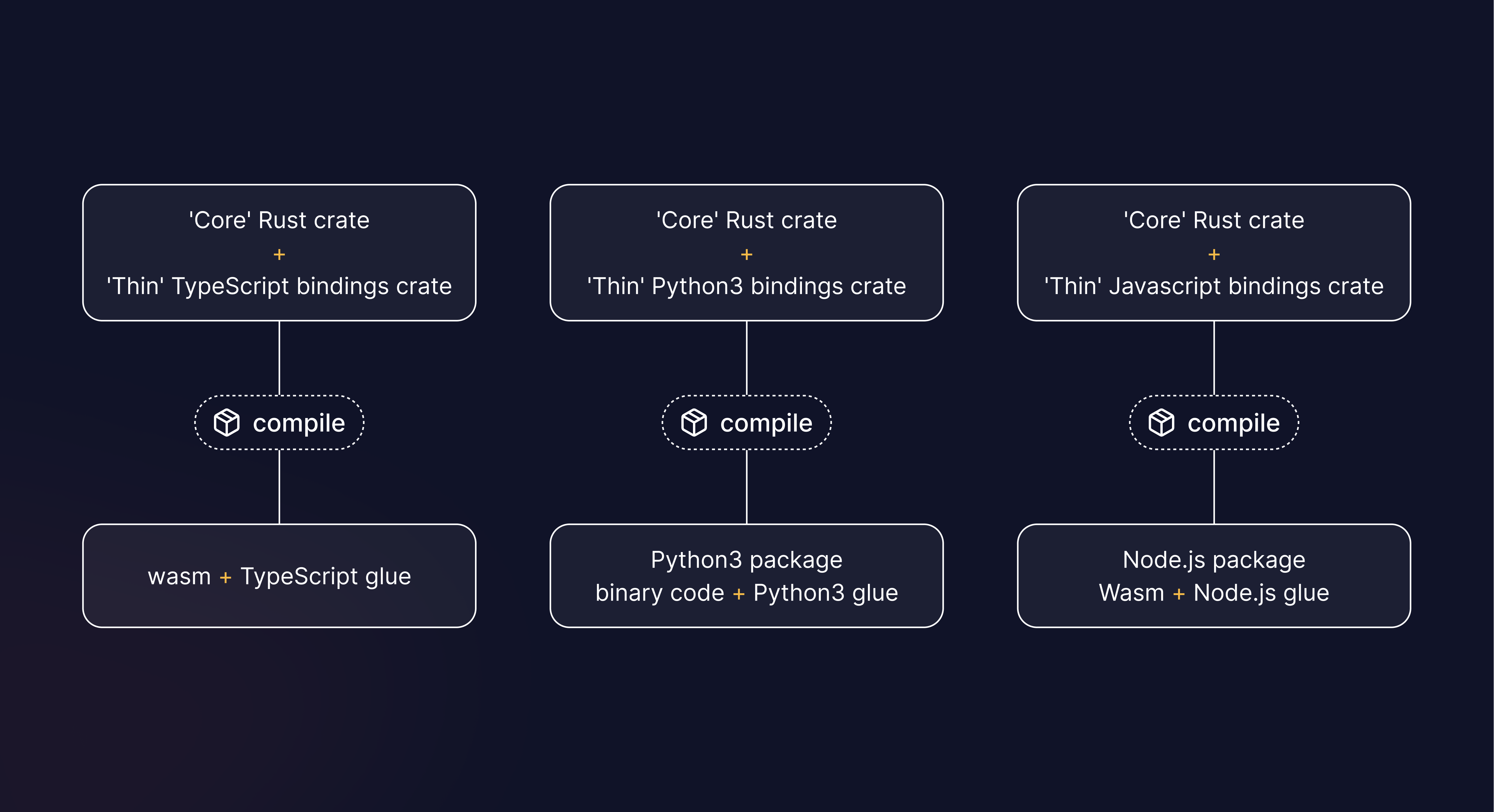

It’s wise to divide the Rust code into multiple crates. The “core” Rust crate should have the functionality you want to provide to each target language. Additional “thin” binding crates should be provided for each target language we aim to support:

In an ideal world, the “thin” crates would be automatically generated for each target language. Unfortunately, this is not currently the case, so we must maintain the “thin” crates ourselves. Every time the main library is changed or updated, we must ensure that the API modifications are reflected in the “thin” crate. This is not ideal but workable, although it does violate the DRY principle.

Common problems II: different targets

The complication of target platforms having different capabilities is not to be overlooked. For instance, in Python, we might want to save Triangles to the local file system. This would require an extension to the core crate, but that feature couldn’t be directly supported in the TypeScript deployment. Instead of moving the extension to the “thin” Python crate, and duplicating that code in other “thin” crates that could access file system (such as Node.js), we incorporate this code into the core crate, and control whether it’s available or not when building a particular target using feature flags.

We must also consider the issue of different bindings implementing the same function in different ways. The time function, which returns the current time, is a good example of this. Rust has access to the operating system, which we can directly avail of in the Python package, but not in the Wasm package. Therefore, when deploying the Rust code to Wasm, we rely on JavaScript providing a time method for use.

The Birthday Book application

Enough preliminaries. If something was unclear in the general discussion, I hope it will become clear with some code samples.

We are going to create a simple “Birthday Book” application, which lets you manage a list of users and their corresponding birthdays. The core of the Rust implementation looks something like this:

pub struct Friend {

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

pub last_name: String,

pub birthday: Option<String>,

}

pub struct Book {

owner: String,

last_edited: u64,

friends: HashMap<String, Friend>,

}

impl Book {

/// Creates a new empty Book

pub fn new(owner: &str) -> Book {

todo!()

}

/// Creates a Book object from it's JSON representation

pub fn from_json_str(json_str: &str) -> Result<Book, String> {

todo!()

}

/// Returns a JSON representation of the Book object

pub fn to_json_string(&self) -> Result<String, String> {

todo!()

}

/// Gives me the list of my friends with a particular last name

pub fn friends_with_last_name(&self, last_name: &str) -> Vec<Friend> {

todo!()

}

/// Adds a new friend, fails if you have the friend in the book

pub fn add_friend(&mut self, new_friend: Friend) -> Result<(), String> {

todo!()

}

// Returns the book's owner

pub fn owner(&self) -> String {

todo!()

}

}

We have an owner of the Book, as well as a last_edited timestamp. All these methods are available via the public API of our library. Additionally, we wish to include:

impl Book {

/// Reads the Book from disk

pub fn read_from_file(file_path: &str) -> Result<Book, String> {

todo!()

}

/// Saves to Book to disk

pub fn write_to_file(&self, file_path: &str) -> Result<(), String> {

todo!()

}

}

These two will only operate effectively in an environment with access to a file system. Although the exact API details are not essential right now, it’s worth noting that the API is incomplete: we need to add methods to delete, update, etc.

Before implementing bindings for various languages, we must address the issue of different targets. As discussed, some targets, for instance Wasm in the browser, do not have access to a file system (this statement is not entirely accurate). Moreover, Wasm lacks random number generation and time functions. We can resolve this predicament in Rust via conditional compilation, which is similar to #if, #ifdef, etc. directives available in C/C++.

In our case, we could use one of two different approaches for conditional compilation: compiling based on the architecture or compiling based on features. We will opt for the former.

We will have two different targets: wasm32 and not_wasm32. We assume that wasm32 runs in the browser environment.

The not_wasm32 target implementation resembles:

// not used in the code sample, but would be required

// for the real implementation

use std::fs;

use std::time::SystemTime;

use uuid::Uuid;

use crate::Book;

/// Returns The Current Epoch Unix Timestamp

/// Number of seconds January 1, 1970 00:00:00 UTC.

pub(crate) fn get_timestamp() -> u64 {

todo!()

}

pub(crate) fn uuid4() -> String {

Uuid::new_v4().to_string()

}

impl Book {

/// Reads the Book from disk

pub fn read_from_file(file_path: &str) -> Result<Book, String> {

todo!()

}

/// Saves to Book to disk

pub fn write_to_file(&self, file_path: &str) -> Result<(), String> {

todo!()

}

}

The above code depends on the following features, not available in Wasm:

uuid4()depends onUuid::new_v4(), requires random number generationget_timestamp()depends onstd::time::SystemTimeread_from_file()andwrite_to_file()both depend on file system access

The wasm32 target would look like:

use js_sys::Date;

/// Returns The Current Epoch Unix Timestamp

/// Number of seconds since January 1, 1970 00:00:00 UTC.

pub(crate) fn get_timestamp() -> u64 {

return (Date::now() / 1000.0) as u64;

}

pub(crate) fn uuid4() -> String {

let crypto = web_sys::window()

.expect("No window object")

.crypto()

.expect("Crypto no present");

crypto.random_uuid()

}

Note:

- We’ve implemented

get_timestamp()by calling JavaScript runtime code (js_sys::Date) - It should be possible to support file I/O in browser-based Wasm using the file API. If you’re feeling adventurous, why not try to implement these two functions yourself? We’d love to take a look at your PR!

TypeScript bindings

Wasm is a first-class citizen when it comes to Rust, documentation, examples and possibilities are endless. It can be daunting to sift through all the material available online, so this post and its accompanying code should help you get started.

We will use wasm-bindgen and wasm-pack. Along with Rust and a recent version of Node.js, you will need to install wasm-pack.

To facilitate the conversion of TypeScript objects into Rust and vice versa, we use tsify. Other alternatives such as ts-rs exist, but once you are able to exchange numbers and strings between the two languages, then additional tooling is not necessary.

In the case of our project, which consists of around 50k lines of code, the bindings for Rust and TypeScript (i.e. wrappers around each API call) total around 1,000 lines of code.

The general structure is:

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub struct WasmBook {

book: Book,

}

#[derive(Tsify, Serialize, Deserialize)]

#[tsify(into_wasm_abi, from_wasm_abi)]

pub struct WasmFriend {

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

pub last_name: String,

pub birthday: Option<String>,

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

impl WasmBook {

#[wasm_bindgen(constructor)]

pub fn new(owner: &str) -> WasmBook {

let book = Book::new(owner);

WasmBook { book }

}

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name=fromJSON)]

pub fn from_json_str(json_str: &str) -> Result<WasmBook, String> {

match Book::from_json_str(json_str) {

Ok(book) => Ok(WasmBook { book }),

Err(s) => Err(s),

}

}

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name=toJSON)]

pub fn to_json_string(&self) -> Result<String, String> {

self.book.to_json_string()

}

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name=getFriendCountWithLastName)]

pub fn get_friend_count_with_last_name(&self, name: &str) -> usize {

self.book.friends_with_last_name(name).len()

}

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name=getFirstFriendWithLastName)]

pub fn get_first_friend_with_last_name(&self, last_name: &str) -> Result<WasmFriend, String> {

todo!()

}

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name=addFriend)]

pub fn add_friend(&mut self, friend: WasmFriend) -> Result<(), String> {

todo!()

}

}

The code should be self-explanatory; however, some key points are worth emphasizing. We decorate methods and classes to automatically generate glue code that serializes and deserializes data.

We must either wrap our types, as I did with WasmBook, or create a new type with the same parameters, as with `WasmFriend. In the latter case, we may find it useful to leverage the from/into traits for a more streamlined implementation.

impl From<Friend> for WasmFriend {

fn from(value: Friend) -> Self {

WasmFriend {

name: value.name,

email: value.email,

last_name: value.last_name,

birthday: value.birthday,

}

}

}

Note that in this case those types are going to be exposed to the user, so you might want to use better names. You could even use Book and Friend by importing the other as use book::{Book as RustBook, Friend as Rust Friend};. Unlike wasm-bindgen, tstify allows us to pass and receive objects as parameters. If the call fails (as indicated by the returned Result object), an exception will be thrown on the TypeScript side.

If you wish to learn more about Rust to WebAssembly without wasm-bindgen, I highly recommend reading Surma’s post.

Python bindings

We’ll use PyO3 and maturin to create our Python bindings.

The code in our case looks something like:

#[pyclass]

pub struct PyBook {

book: Book,

}

#[pyclass]

#[derive(FromPyObject)]

pub struct PyFriend {

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

pub last_name: String,

pub birthday: Option<String>,

}

#[pyfunction]

fn create(owner: &str) -> PyBook {

PyBook {

book: Book::new(owner),

}

}

#[pyfunction]

fn from_json_string(json_str: &str) -> PyResult<PyBook> {

match Book::from_json_str(json_str) {

Ok(book) => Ok(PyBook { book }),

Err(s) => Err(PyValueError::new_err(s)),

}

}

#[pyfunction]

fn read_from_file(file_path: &str) -> PyResult<PyBook> {

match Book::read_from_file(file_path) {

Ok(book) => Ok(PyBook { book }),

Err(s) => Err(PyValueError::new_err(s)),

}

}

#[pymethods]

impl PyBook {

pub fn to_json_string(&self) -> PyResult<String> {

self.book.to_json_string().map_err(PyValueError::new_err)

}

pub fn add_friend(&mut self, friend: &PyAny) -> PyResult<()> {

todo!()

}

pub fn write_to_file(&self, file_path: &str) -> PyResult<()> {

todo!()

}

pub fn get_first_friend_with_last_name(&self, last_name: &str) -> PyResult<PyFriend> {

todo!()

}

pub fn get_owner(&self) -> String {

self.book.owner()

}

}

/// A Python3 module implemented in Rust.

#[pymodule]

fn pybook(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add("__version__", env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION"))?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(from_json_string, m)?)?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(create, m)?)?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(read_from_file, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}

It’s worth noting the similarity between the Python and TypeScript bindings structures. Though their decorator names differ, the functions they perform are analogous. I opted to have creators appear outside of the class, as this is a more “Pythonic” approach. Additionally, methods that can throw an exception must be wrapped in PyResult.

Taking into account the documentation and the above, it should now be relatively easy to construct Python extensions for any Rust library.

Node.js bindings

Node.js is the most challenging of the three platforms to target. We will use napi-rs, which is currently more comprehensive and easier to manage than neon. The term ‘napi-rs’ originates from its use of the Node API, which is the latest Node.js abstraction.

Without further delay, the Node.js bindings for Rust:

#[napi]

pub struct NodeBook {

book: Book,

}

#[napi(object)]

pub struct NodeFriend {

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

pub last_name: String,

pub birthday: Option<String>,

}

#[napi]

impl NodeBook {

#[napi(constructor)]

pub fn new(owner: String) -> Self {

let book = Book::new(&owner);

NodeBook { book }

}

#[napi(factory)]

#[napi(js_name=fromJSON)]

pub fn from_json_str(json_str: String) -> Result<NodeBook> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(js_name=toJSON)]

pub fn to_json_string(&self) -> Result<String> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(js_name=getFriendCountWithLastName)]

pub fn get_friend_count_with_last_name(&self, name: String) -> i32 {

self.book.friends_with_last_name(&name).len() as i32

}

#[napi(js_name=getFirstFriendWithLastName)]

pub fn get_first_friend_with_last_name(&self, last_name: String) -> Result<NodeFriend> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(js_name=addFriend)]

pub fn add_friend(&mut self, friend: NodeFriend) -> Result<()> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(js_name=writeToFile)]

pub fn write_to_file(&self, file_path: String) -> Result<()> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(factory)]

#[napi(js_name=readFromFile)]

pub fn read_from_file(file_path: String) -> Result<NodeBook> {

todo!()

}

#[napi(js_name=getOwner)]

pub fn get_owner(&self) -> String {

self.book.owner()

}

}

Using wasm-bindgen with Node.js requires slight adjustments; for example, passing String to the methods instead of &str. It is also worth noting that an external library (such as tsify for wasm-bindgen) is not necessary to expose a TypeScript object.

Final words

If you have ever worked with Python extensions in C/C++ or Node.js add-ons using gyp or a related tool, you’ll be delighted to see how easy it is to interoperate with Rust. Although we haven’t discussed how to package the resulting code for production in this post, it is relatively straightforward and can be done either manually or with existing tools.

It is worth noting that these technologies are constantly evolving, so if you’re reading this in 2024 or later, there may be better ways to do some of the activities we have outlined here. For example, there are two potential alternatives,wasmer and wasmtime, which enable code written in any language that can be compiled to WebAssembly and run in virtually any other language. For more information, take a look at this video.

That’s all for today!